The Long View

Guided Tour of Macintosh

Let’s say you'd never used a hammer. Somewhere in your brain, there are neurons that solve the equations of motion for your arm, but they are only correct when it moves without a hammer. The neurons have to predict a set of muscle contractions that will place your hand on a target selected visually, striking that spot with just the force and velocity you wish. You can do it whenever you want to. Now you pick up a hammer for the first time, and try to place its striking surface on some visually-selected point, with some specified force. But the weight and moment of the hammer have changed the equations of motion for your arm. Your brain flubs the calculation, and the hammer hits the wrong place. With sufficient practice, you become good at it. The hammer goes where you want it to, seemingly effortlessly. Your brain has learned to solve the new equations of motion for the arm-hammer combination, and the hammer has become an effective extension of your arm. We say you have learned to use a hammer, but what have you learned? Could you teach it to somebody else? Could you have learned it another way? For example, if you read everything there is to know about hammers and about their effects on the equation of motion, would that help? Of course not. This kind of learning is something different.

Intuitive

The Macintosh was supposed to be a different kind of computer, one that didn't require you to learn anything new. This sounded good to people, because learning requires effort and nobody wants to have to learn anything new. There was even a television advertisement based on that. It showed an IBM PC, and there was a voice that said: "This is a highly sophisticated business computer, and to use it all you have to do is learn this". At this point a familiar stack of 3 thick loose-leaf technical manuals falls onto the table next to the PC. Then it showed a Macintosh, and the voice says "This is Macintosh from Apple. Also a highly sophisticated business computer, and to use it, all you have to do is to learn this". The thin Macintosh user's manual drops on the table next to it. What the advertisement is saying was that the Macintosh did not require you to learn much of anything new to use it. Macintosh users said that it was “intuitive”, and that command line operating systems were not. Nowadays, it is very common to hear somebody say that some program or operating system is intuitive. The other day a student told me that the Windows user interface is intuitive, but the Mac OS X interface is not. What do we mean when we say something is intuitive? Does it mean that any intelligent being from any place in the universe could figure it out because it is based on universal concepts fundamental to thought, like Kant’s notions of time and space? No, nothing like that. Intuitive just means that you don’t have to learn anything new. So if you already know how to do it, that’s intuitive, and otherwise not. Sometimes I hear scientists say that some finding or interpretation is intuitive, and they mean that to be a good thing. No it isn’t. It means it is something you already knew. Scientists should not get excited about discoveries that are intuitive. They should be excited about non-intuitive things. A real discovery has to be non-intuitive, meaning that it is really original, not something you already know.

Listen, Experiment, and Enjoy Learning

It was true that the Macintosh was easier, because to use it, you didn’t have to memorize a bunch of unfamiliar written commands and their syntax. On the other hand, command-line interfaces, including MSDOS on the IBM PC, didn't require you to learn to do anything new. If you could type, you could type the commands. The commands were static. They just sat there while you typed them, and then you hit return and they would execute without any further help from you. Learning to use the IBM PC was like learning to read and write in a new language that used the same character set as one you already know. You just needed to learn the new words. On the other hand, learning to use the Macintosh didn't require that you learn a lot of new words. It was more like learning to use a hammer. Your hands and eyes had to be trained to view the screen and mouse as an extension of your eyes and arm. You needed some practice.

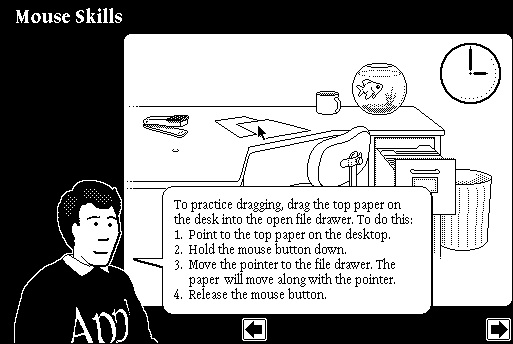

Today it's easy to believe that there wasn't anything to this. Everybody now uses a Macintosh or Macintosh-like computer, and using mice, menus, or virtual buttons with words or pictures on them seems very natural and familiar. So does riding a bicycle, after you learn to do it. Maybe you don’t remember learning to use the Macintosh user interface. Maybe you learned to use a computer when you were young, at the same time you were learning a lot of other things, like riding a bicycle or throwing a ball. But you did have to learn it, and in 1984, when the first set of adults were learning to use the Macintosh, practically nobody had ever used a mouse before, or knew how to use it to control the location of a pointer on the screen. They might have guessed that moving the mouse would move the pointer, but nobody knew that clicking the mouse button would select the thing the pointer was over. They didn't know what a menu looked like, or that if you held the mouse button down over one, a list of choices would appear. Nobody knew how to use the mouse and mouse button to drag things around on the screen. And nobody knew that double-clicking would execute a program or use a program to open a document. New Macintosh users had to learn all that stuff. But it wasn't like just learning some new words. You couldn't really learn it by reading about it, so there wasn't much point in putting all that in a manual. The best way was the same way you learn to use a hammer. You watch somebody else do it, then you try it yourself.

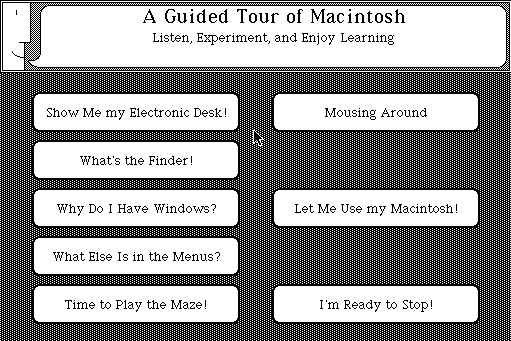

Accordingly, the real manual for the Macintosh wasn't a book. That was the secret hidden by the television advertisement. To use the Macintosh, you didn't even need to read that little book that dropped onto the table. In fact, reading that book wouldn't help much and most people didn't do it. The real manual for the Macintosh was a computerized training session that came on a diskette and a cassette tape. The combination was called Guided Tour of Macintosh. The cassette tape was like one of those audio-guided tours in which you put on a headset and walk around, and a recorded voice tells you what you are looking at. You have to pause the audio if you linger too long at one part of the attraction. Then you turn it on again when you are ready to move on. The attraction in this case was something happening on the screen of the Macintosh. When you inserted the Guided Tour diskette, it didn't launch the regular Finder and bring up the desktop and menu bar. Instead, it brought up a screen with the familiar long and angular face that greeted us in alerts boxes, and some buttons letting you execute a series of automated demonstrations. The subtitle advised you to "Listen, Experiment, and Enjoy Learning".

Lisa Guide

As in most things Macintosh, the Guided Tour was inspired by a similar thing provided with the Lisa, the Lisa Guide. I don’t have a Lisa, and I can’t remember ever using the Guide when I briefly had the use of a Lisa a long time ago. For some reason, I can’t get the Lisa Guide to boot in the otherwise wonderful Lisa Emulator. So everything I know about it comes from the Guidebook site. The Lisa Guide did not have a cassette tape, so you had to read your instructions. But it was interactive, and could tell if you had done what you were supposed to do. It rewarded good pointing, clicking and dragging with move to a new screenful of text and a little textual validation. Sometimes, the cursor would move by itself, and the user was asked to leave the mouse alone. After sequential demonstrations and some practice at pointing, clicking, and dragging, there were a series of sections showing all the basic Lisa skills, including using pull-down menus, creating new documents, saving your work, and deleting files. The overall structure of the Lisa Guide was repeated in all the Macintosh Guided Tours for years afterwards.

The Guided Tour of Macintosh

The first Guided Tour came with the original 128k and with the 512k Macintosh. It was created using a unique method, called Journaling. The Journaling mechanism was built into the Macintosh, and was the basis of its first macro or scripting technology. Journaling consisted of a driver and a couple of system globals called JournalFlag, and JournalRef. If JournalFlag is zero, journaling is off. A negative value of JournalFlag causes events to be played back by the journaling driver, and the Macintosh’s mouse and keyboard do nothing. A positive value of JournalFlag restores function to the mouse and keyboard, but also passes all events to the journaling driver for storage. The format for storing journaled data is up to the journaling driver. JournalRef contained the resource ID for the journaling driver. It’s possible to experiment around with the journaling driver used for the Guided Tour. If you have a Guided Tour disk, you can find the driver in its System file. Its name is .Journal and its ID number is 20. Copy the driver out of that System file (using Resorcerer or ResEdit) and paste it into the System file of another disk. Rename it Journal (without the initial period) and it becomes a desk accessory. When running, it installs a menu that lets you record or playback events from within any program.

If you record some events, you acquire a file called journal.jrnl. I guess this must the script that was generated during journaling, but I can’t make any sense out of it.

Journaling just recorded events. So you couldn’t make a Guided Tour with that alone. There had to be a program running, that could react to the events. In the old Macintosh, any program named Finder and located on the startup disk would be launched at the end of the boot sequence. So the Guided Tour consisted of a program as well as a set of journaled events, and the program could switch between taking its events from the journal to expecting them to come from the mouse and keyboard, just by changing the value of JournalFlag. The Guided Tour disk had a special Finder, that was the real Guided Tour program.

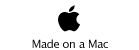

A similar Guided Tour disk was provided for the two programs that came with the original Macintosh, MacPaint and MacWrite.

Macintosh Plus, SE and Mac II

Event journaling was a very cool feature of the Macintosh operating system, and became the basis of Macintosh scripting programs in the pre-System 7 world. But it was abandoned as the basis of the Macintosh Guided tour pretty quickly. Early versions of the Macintosh Plus came with a diskette and cassette tape combination similar to the original Guided Tour. But starting in 1987 the Macintosh Plus came with System 4.0 and Finder 5.4 and the Guided tour was replaced by Your Apple Tour of the Macintosh Plus. This new training disk employed a new technology developed by a third party, MacroMind. MacroMind was the creation of Jamie Fenton, Marc Canter and Mark Pierce, and their first product was called VideoWorks. Apple contracted with them to produce the new Mac Plus version of the Guided Tour using their new product, and it was as much a demo for VideoWorks as it was an education for new Macintosh users. VideoWorks evolved into Director, and ultimately MacroMind was purchased by Adobe, where it lives on to this day. The inventors of VideoWorks didn’t all stay with MicroMind through all that. Jamie Fenton had programmed microprocessor-powered pinball machines and the classic Bally Arcade game console in the 1970’s, and after MacroMind worked with Alan Kay on a Smalltalk-80 kids’ programming environment called Vivarium. Then she worked at Kaleida on the Script-X authoring system and then on the LEGO Mindstorms projects. Marc Pierce later designed the classic Dark Castle games for Macintosh (programmed by Jonathan Gay), and many subsequent games for Arcade and consoles. His current company, superhappyfunfun creates games for mobile devices. You probably have one or more of their games on your phone. And of course they sell a modern version of Return to Dark Castle for the Macintosh.

Your Apple Tour of the Macintosh Plus was a much more advanced teaching tool. This new version didn’t use a cassette tape for voice narration. It used the primitive sound effects available in VideoWorks, and written narration on screen, similar to that used in Lisa Guide (although shorter and greatly enhanced by cool graphics). But it taught the same lessons. It started with pointing, then clicking, then dragging. After that it had little modules on using windows, menus, throwing things away, organizing your files, and using desk accessories.

The Your Apple Tour disk, slightly altered, was provided with the Macintosh Plus, various Macintosh SE models, and the Macintosh II models.

Macintosh Basics

Apple Guide used something like journaling. The System 7 version of event recording was AppleEvents. Apple Guide interacted with programs by sending and receiving AppleEvents. The help user interface and the database that allowed the user to interact with it could be integrated with a program using AppleEvents. For the general Macintosh Guide that came with every computer, the interaction was with the Finder, control panels, and other standard operating system code. Because AppleEvents could specify their recipients, Apple Guide could work across application boundaries, and could guide users through tasks that required more than one program, or a program and a general operating system feature. Apple Guide was the ultimate interactive guided tour. But it was also an online help system, and online help was doomed, abandoned by users and by programmers. OS X still has something called help, but it’s an empty shell -- just a hook to some html, that could be installed on a user’s computer, or a link to the programmer’s website. Apple makes no attempt to standardize help.

Video Tours

It’s instructive to look at Apple’s current set of instructions for the Macintosh and iPad Guided Tours, that are on line at the Apple website. These are half-advertisement, half-instruction. They are as much directed at potential buyers as they are owners of Apple equipment. They show happy customers productively using their Apple equipment for all kinds of fun and productive work. To the person familiar with the original Macintosh Guided Tours, the most remarkable thing about them is just how non-interactive they are. The internet, which is optimized for interactive computing, is used by Apple just to run a bunch of videos showing other people using their Macs or iPads or phones. They are video versions of the big old books that fell on the table next to the IBM PC. “The Macintosh is a sophisticated business computer. To learn to use it, all you have to do is passively watch this set of videos, and be able to reproduce the actions you saw performed there.”

BG -- basalgangster@macgui.com

Wednesday, August 31, 2011