The Long View

Fixing Canvas

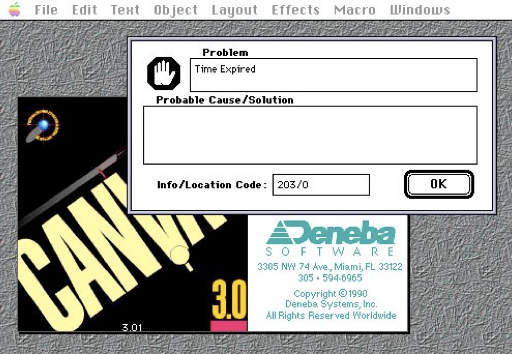

In 1990, I bought a copy of Canvas, version 3.01. It wasn’t a subscription. It was a license in perpetuity. Nonetheless, a little while ago, when I tried to launch my copy of Canvas, it told me that Time had Expired, which it said had an Info/Location Code of 203/0, and it offered no probable causes or solutions. When I said that was Ok, it quit. I know I shouldn’t have agreed. I knew that time had not really expired. But there was no button available for registering a disagreement. Canvas 3.01 claims that Time is Up, and that is that. I would contact Deneba Software, in Miami Florida, to discuss it with them, except they don’t exist anymore. According to Wikipedia, Deneba was acquired by ACD Systems of Victoria, B.C. Canada in 2003, and they have not published a Mac version of the program since 2005. There was a total rewrite of the program in 1996 anyway, so probably there was nobody around there that knew what to do about my problem. Probably they would have suggested that I buy a new version of the program. But Canvas was totally ruined by the 1996 rewrite, and as a result I dumped it and switched to Adobe Illustrator/Photoshop. But I still have some old Canvas documents from back in the 1990’s, and I want to use them. I want to run my old version of Canvas, not buy a new one.

What are my rights in this situation? I don’t remember-- did I promise never to reverse engineer Canvas? If I did, do I still have to honor that promise, given that Deneba Systems apparently planted a time bomb in a program that was sold to me under a permanent right-to-use? And most importantly, have they not violated whatever agreement we had by saying something as stupid and inane as “Time Expired”? Here I am, here it is, time is still going by, as always. Whatever you might believe about the approach of the End of Time, I think we can all agree that it has not happened as of the time I am writing this.

I think it’s okay for me to fix this myself

I’m not a lawyer, but on the basis of the above argument, I declare that I have a right to do whatever needs to be done to make Canvas 3.01 work again. So here we go.

But now I’m curious about what happened. Did Deneba really put a time bomb in my program, or was it just some kind of programming error that didn’t get caught for 14 years. I’m going to conduct an investigation.

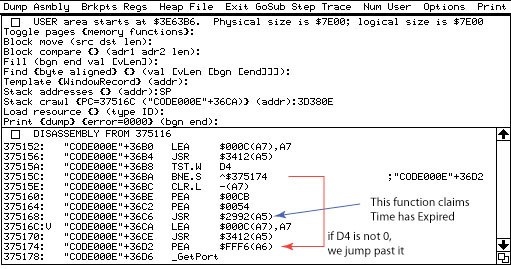

To do it, I have to understand func1-4, and those two local variables that get compared. But none of those functions are in this segment. They are accessed via the jump table. Now this is a place where MacNosy would would be helpful. It could disassemble the entire program, and resolve all the addresses so we could look at each of those subroutines in turn, no problem. But Canvas is a big program, and when I try to look at it in MacNosy, it crashes MacNosy. I have to do it in TMON.

The Investigation

Next the code uses GetResource to read in a resource of type ‘toly’, with resource ID 1011. That resource gets read in, and its handle gets stored in A4. Then that handle is pushed onto the stack,and a second function, func2 gets called. The same method described above reveals that func2 simply locks the handle.

Hmm. So the ‘toly’ resource contains a date/time record. A date/time record consists of 7 16 bit integers. The first is a year since 1904, with 2040 as the maximum year possible. The next is 1 - 12 for the month, then 1 - 31 for the day, then 0 - 23 for the hour, then 0 - 59 for minutes, 0 - 59 for second, and 1-7 for the day of week. Let’s open the resource in ResEdit or Resourcerer and get the ‘toly’ resource’s value and see if we can make sense of it. The value is '07D4 0008 001F 000C 001E 0000 0001'. So the date recorded there will be 2004, August 31,12:30:00. This may explain why my copy of Canvas isn’t working. That date has passed. But surely Deneba didn’t purposely program an expiration date of 2004 for Canvas 3.0, back in 1990. Just to check,, I try changing the resource to a later date, by adjusting the contents of the ‘toly’ resource. Changing the first integer to a bigger number, like 07F8 (2040, the last year supported by date/time records) makes the program work. Once again, I could stop here. I now have two working solutions to the problem, but it’s starting to look like Deneba intended things to go wrong in 2004, so now I want to see what those comparisons are.

The next function, func4, just unlocks the handle. The next thing is a comparison. The value of our ‘toly’ date in seconds is compared to the value held in local variable $FFFA(A6). If it is less than today’s time, we jump just past the line that is setting D4 to 1 (and messing us up). So sure enough this subroutine is comparing today’s date with an expiration date for the program, stored in the ‘toly’ resource. This isn’t some kind of error, or sloppy programming. The ‘toly’ resource was probably intended for a temporary trial license to give potentials customers a 30 day free trial license. But what could be the point of making the program expire for regular customers on August 31, 2004? Certainly this isn’t intended to force customers to update their version of Canvas. The software update cycle was then and is now quite a bit shorter than 14 years. Probably, the easiest way to give people a ‘permanent’ license was to put a long-distant date in the expiration date. 2004 was probably just picked as a long-distant time, or maybe the programmers even intended to use the longest-distant possible date in a date/time record (2040), and transposed the last two digits.,

The Verdict

Deneba Software, of Miami Florida, you are hereby charged with the following crimes against your customers:

-

A. Creation of a laughably stupid error message, “Time Expired”, and enclosing it in a badly designed dialog box with a meaningless error number and a place for Possible Cause and Solution, but then entering nothing there.

-

B.Lazy and irresponsible programming, that caused a feature of your program that was intended for trial periods to be applied against programs running with a permanent license.

-

C.Violating your own license agreement by terminating operation of your program for customers who have purchased a permanent license

Do you have anything to say in your defense? Uh-huh, I didn’t think so. You have been found guilty of all charges. You are hereby sentenced to, within 6 years of committing these crimes, create a new version of your software that is so bad that your customers all immediately looking for another solution. Over the following 5 years you will try to undo the damage, but fail. In the end, you will be reduced to selling your crappy program to a few hapless Windows users who don’t know any better.

Court is adjourned.

-- BG (basalgangster@macGUI.com)

Saturday, April 10, 2010