The Long View

Smalltalk-80

Everybody knows that in 1979 Steve Jobs and some Apple engineers visited the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center and were shown some of the amazing experimental hardware and software under development there. PARC was working on a number of revolutionary ideas about how to use computers, and there has been a lot said and written about what Jobs and the other saw and how it might have influenced future Apple products including the Lisa and the Macintosh. Maybe they saw an experimental version of the Star networked office system and laser printers. We know for sure that they saw the Smalltalk programming environment. We know that because we have the word of Bruce Horn, who should know (see http://www.folklore.org, article entitled "On Xerox, Apple and Progress").

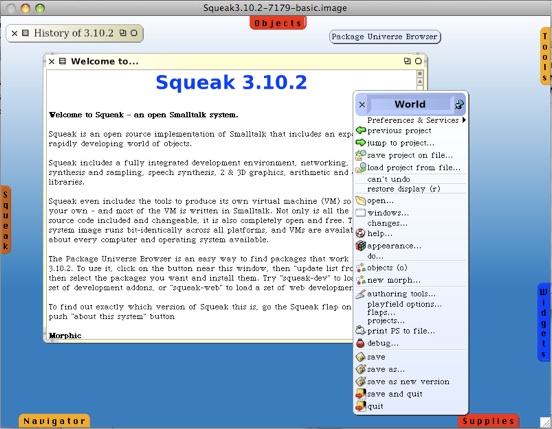

Smalltalk isn't an office computer system. It doesn't include a word processor, a graph-drawing program, or a filing system using a desktop metaphor. It's a programming language, a programming environment, and a simple operating system. It’s intended for use by computer programmers, not office workers. But it clearly had a huge influence on Apple. As a programming language, it is a direct predecessor of Apple’s current favorite, Objective-C, which was designed to be a cross between Smalltalk-80 and C. As a user interface, it is a direct predecessor of the Lisa and Macintosh, and also Windows and X11. Smalltalk pioneered a lot of the key features of nearly all current computer interfaces, including the use of the mouse as a pointer, overlapping movable and resizable windows, cursors, and menus.

Smalltalk also is a predecessor of all modern Integrated Development Environments, including Microsoft's .NET and Apple's XCode. It has an integrated class browser, code editor, syntax checker with built-in spelling correction, and source level debugger. It was originally designed for use in a Xerox’s networked environment, and it treated remote filesystems on servers as the equivalent of local mounted volumes. It kept managed programmers’ source code documents in a built-in database rather than requiring or allowing users to organize files themselves. It presented the entire library of source code, both for the operating system and for user applications in a single browser. In this it presaged programs like iPhoto and iTunes, that relieve users of the need to name documents and organize them into directories. Smalltalk was, and still is, a little miracle. In many ways, computer systems now still fall a little short of fulfilling the promise that was represented by the Smalltalk system.

Apple Smalltalk-80 on the Macintosh

Want to see what Smalltalk-80 looked like? It turns out to be pretty easy to do, if you have a Mac Plus or a working Mac Plus emulator like Mini vMac. Only a couple of years after the legendary 1979 visit, Apple participated in an experimental project with Xerox PARC, Tektronix, Hewlett Packard and Digital Equipment Corporation, in which they implemented Smalltalk-80 on their respective machines. There is a photo of a Lisa (the original Lisa with dual 5.25” diskettes) running Apple's implementation of Smalltalk on page 5 of Adele Goldberg's classic book "Smalltalk-80 The Interactive Programming Environment" (Addison-Wesley, 1984). I guess that it by participating in that experiment, Apple got the rights to build and distribute Smalltalk-80 (version 1) for Apple computers. I don't think that Apple ever distributed the native Lisa version of Smalltalk-80 that is shown in the photo. But on page 53 of the paper documents that came with the "May 1985" Software Supplement mailing to Macintosh developers, there was a note that said this:

"Smalltalk

We are currently developing a version of Smalltalk tailored to the Macintosh computer. In the meantime, in response to requests from several universities, we have released a 'pre-product' version of the Smalltalk-80™ programming system running on the Macintosh and Macintosh XL computers. This is a fairly complete implementation of the Smalltalk-80 system, which we believe to be suitable for student projects and other preliminary experiments with Smalltalk."

Interested parties were instructed to contact Eileen Crombie at Apple. The cost of the program turned out to be $150.00, $50.00 for educational institutions, and it included (it was only available as) a site license. The system that was shipped was marked v0.2. Apparently there had been an earlier version (in March 1985) that ran only in the Mac OS a Macintosh XL (because regular Macs didn't have enough memory). I don't know how anybody found out about that one though, because it was not mentioned in the previous (Feb 1985) software supplement. Smalltalk-80 v0.2 was available starting in August of 1985. There were 2 configurations. The first, called Level 0, would run on a Macintosh 512K, but was only a subset of the entire system. Level 1 required 1 MB or more of memory, and could run on Macintosh XL or any Macintosh with 1 MB of memory. The Mac Plus, with 1 MB of memory standard, was released on Jan 16, 1986. Both level 0 and level 1 could be run with or without a hard disk but a hard disk was required to use the source file. The next version, v0.3, was dated October, 1986, and was the first version compatible with the hierarchical file system, and so would work properly if placed in a directory on a HFS-formatted hard disk. A final version, version 0.4, was dated June 9,1987 and was compatible with the Mac II. After that, there was no further word from Apple about Smalltalk-80 on the mac.

All Macintosh versions of Smalltalk-80 were the original version of Smalltalk-80, called version 1 at Xerox. By the time Apple was offering Smalltalk-80 for the Macintosh, Xerox was using version 2, and it is version 2 that is described in the classic books on the Smalltalk system. I suppose that Apple was restricted to distributing version 1 systems because that was the system for which they obtained a license back at the time of their participation in the experiment. There were small differences between the versions in some menus, and Apple offered a patch that could change the menus to better correspond to the system described in the book. At various times, Xerox or the spin-off Parc-Place Systems offered Smalltalk-80 as a commercial product on the Macintosh and other computers. Their assets are owned by Cincom, who still offers commercial and noncommercial versions of Smalltalk for Windows. They also have a free noncommercial version for Mac OSX, called VisualWorks. It’s a very complete and modern version of Smalltalk. Take a look at http://www.cincomsmalltalk.com.

Setting Up Smalltalk-80 in Mini vMac

To start Smalltalk, double click the Smalltalk-80.image file, not the interpreter, Smalltalk-80. The interpreter is the only Macintosh executable file and it has to be there, but you never directly use it for anything. The image file is a complete representation of the entire state of the system. Everything is there, down to the positions of windows and current values of all the variables. If you update the image file before quitting Smalltalk, when you start it again it will appear just exactly as it did at the moment you saved the image.

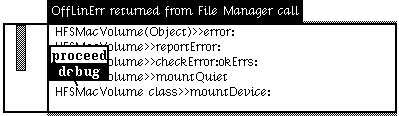

Starting Smalltalk In Mini vMac Results in an Error

Smalltalk on Modern Macs

-- BG (basalgangster@macGUI.com)

Saturday, March 6, 2010